Unguided by any master, the young artist could rely only on his own sense of balance, preserving every atom of felt expression. The results revealed him as a born artist, distinct from those who merely have an ambition to become creators but lack a gift of nature.

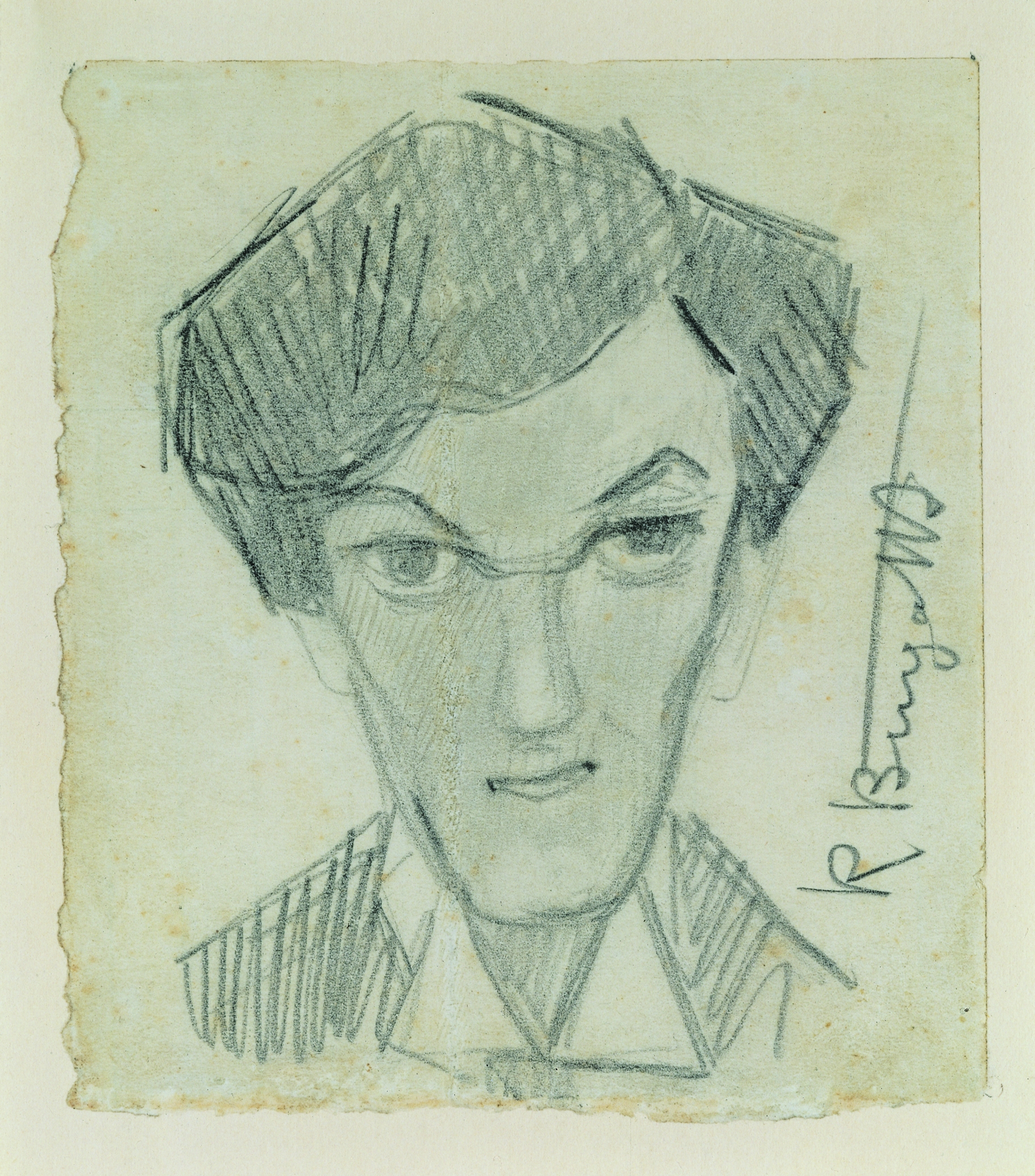

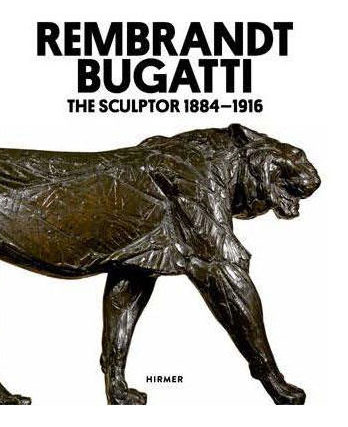

Rembrandt Bugatti was one of the most talented sculptors of the twentieth century. In a career that spanned little more than a dozen years before it was cut short in 1916 by his tragic suicide at the age of 31, he created a prodigious body of work. His art combined huge technical finesse, formal beauty, intensity of expression and subtle stylistic inventiveness.

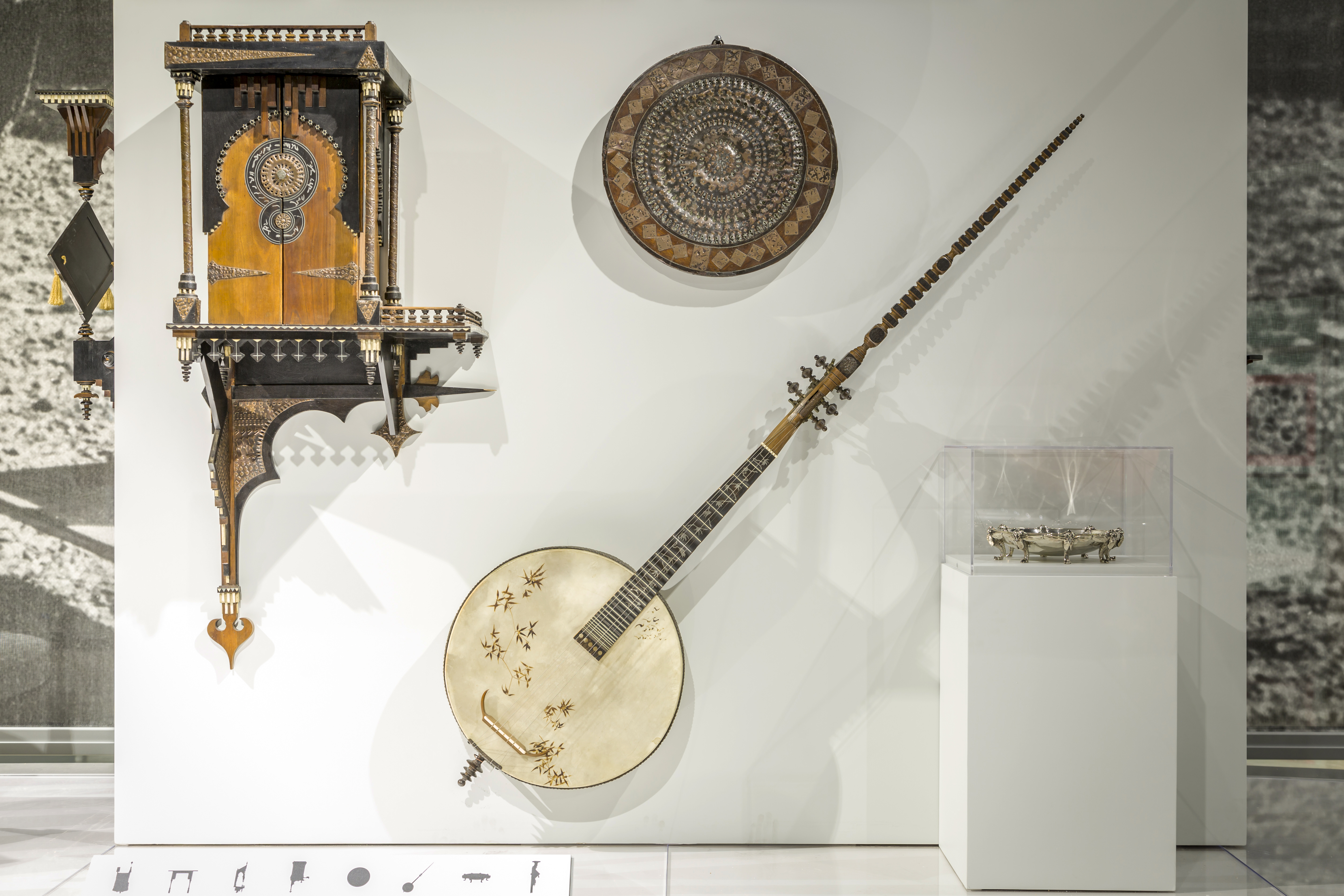

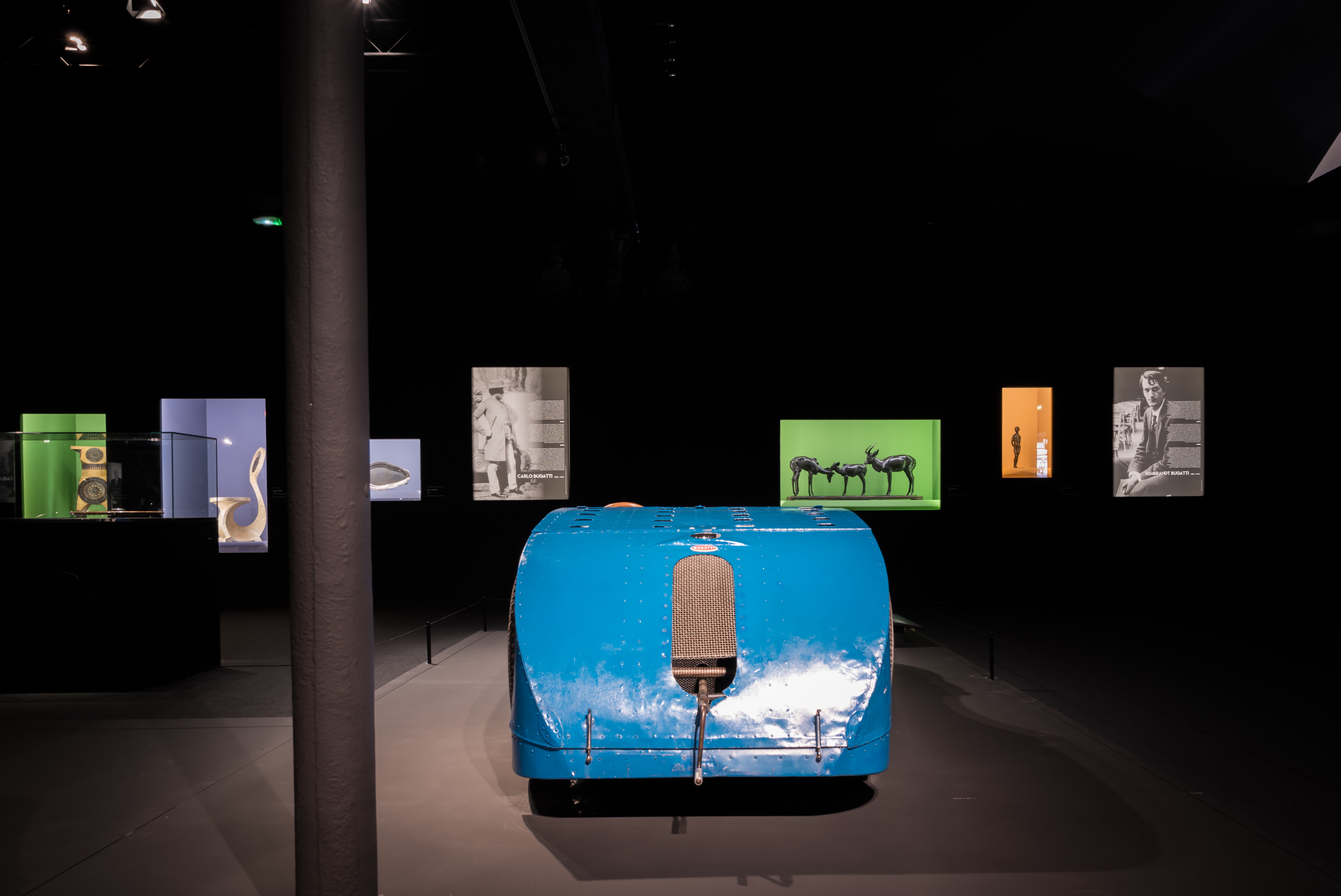

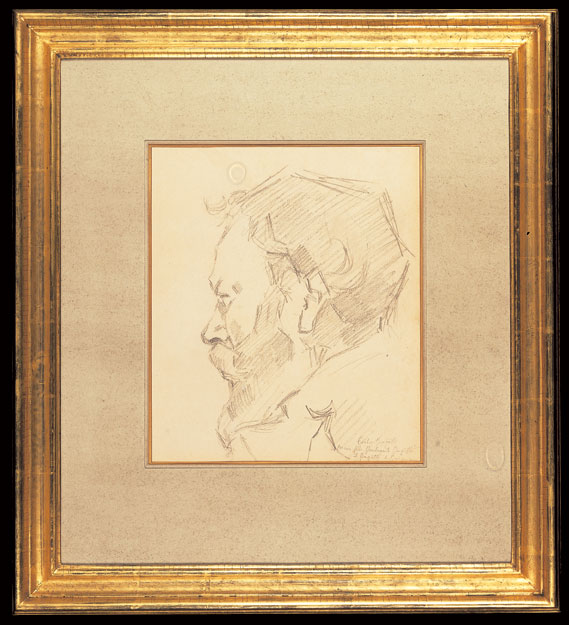

Son of the great fin de siècle designer Carlo Bugatti, who had a huge impact on his talent, and younger brother of the epoch-making car designer Ettore Bugatti, the audaciously named Rembrandt has emerged as a shadowy personality in the history of the European artistic community before the First World War. For too long after his death he was often dubbed ‘the other Bugatti’, since little was known about his life, and he did not fit into recognised art-historical movements.

Born in Milan in 1884, Rembrandt Bugatti was one of the most talented sculptors of the twentieth century. In a career that spanned little more than a dozen years before it was cut short in 1916 by his tragic suicide at the age of 31, he created a prodigious body of work.

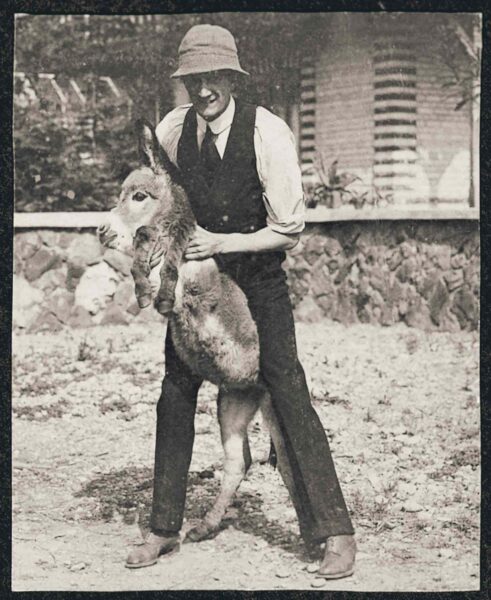

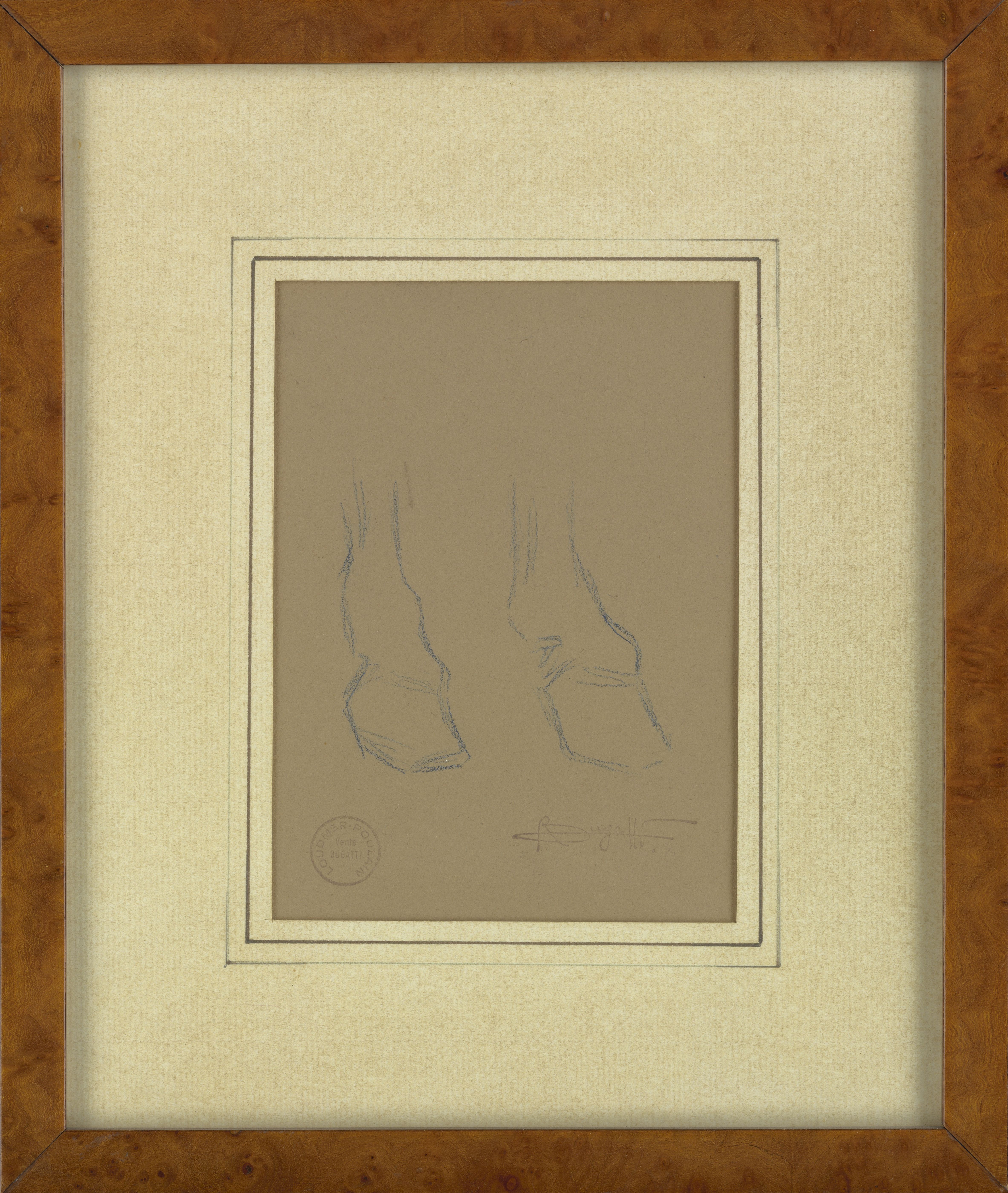

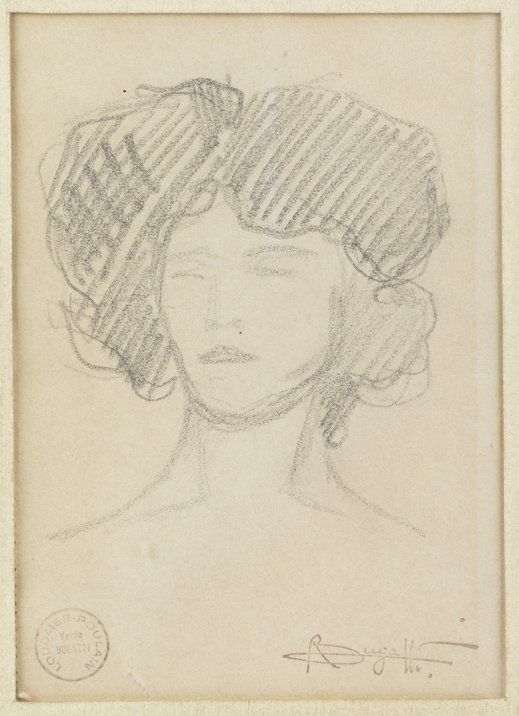

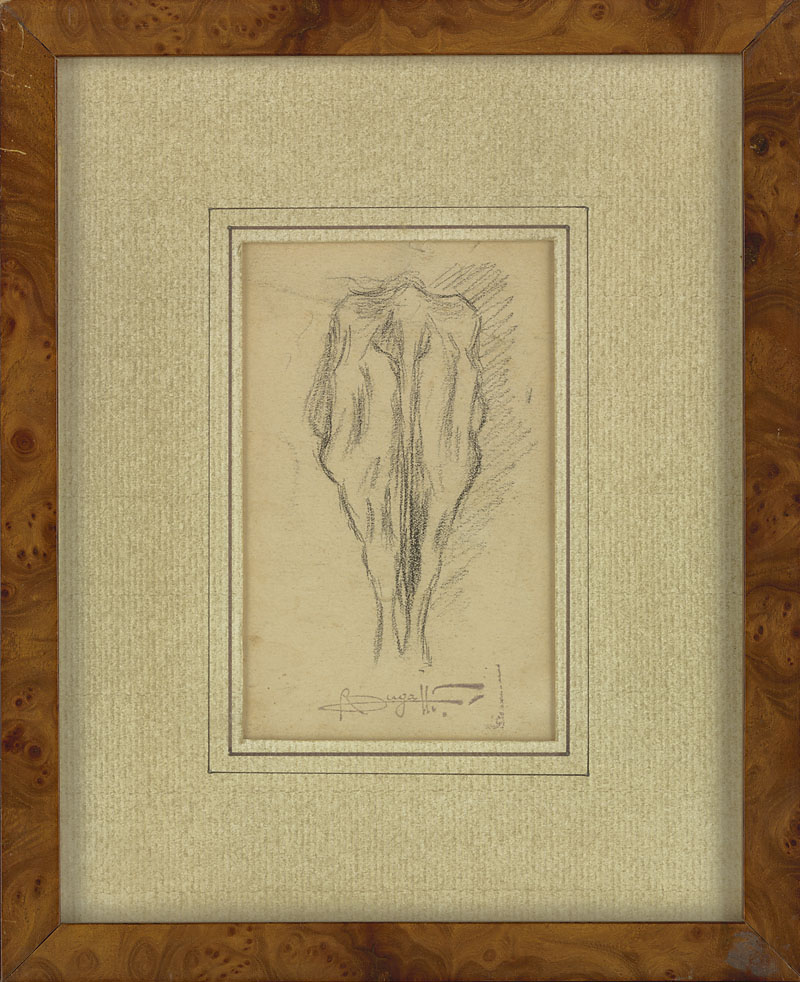

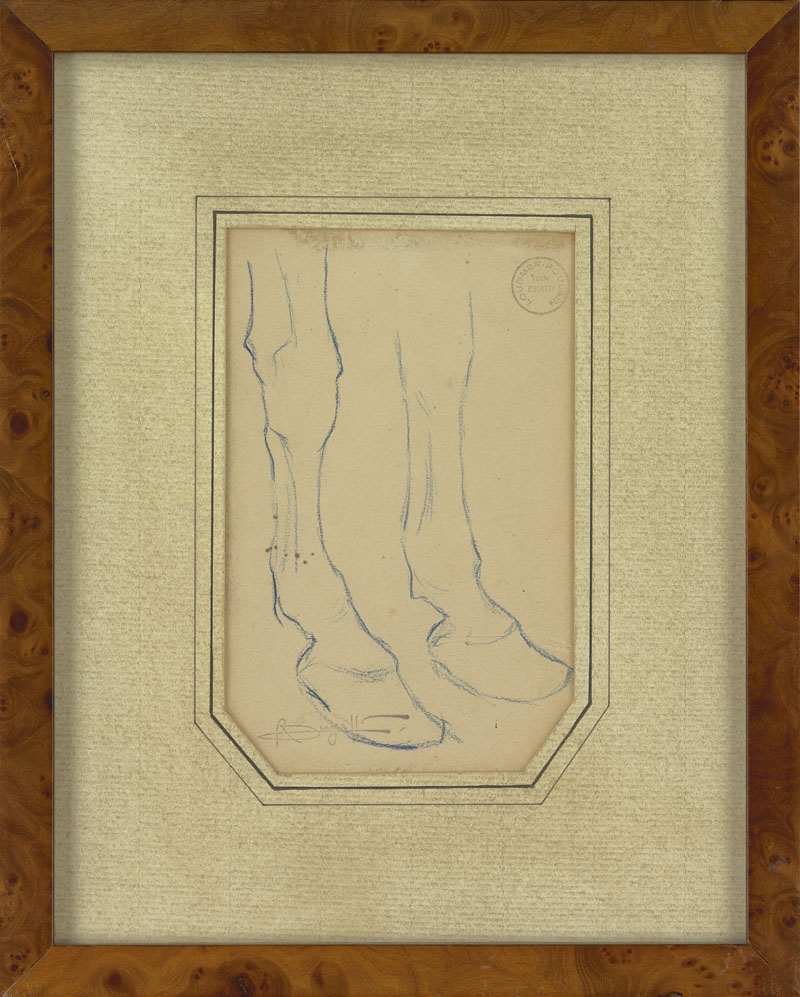

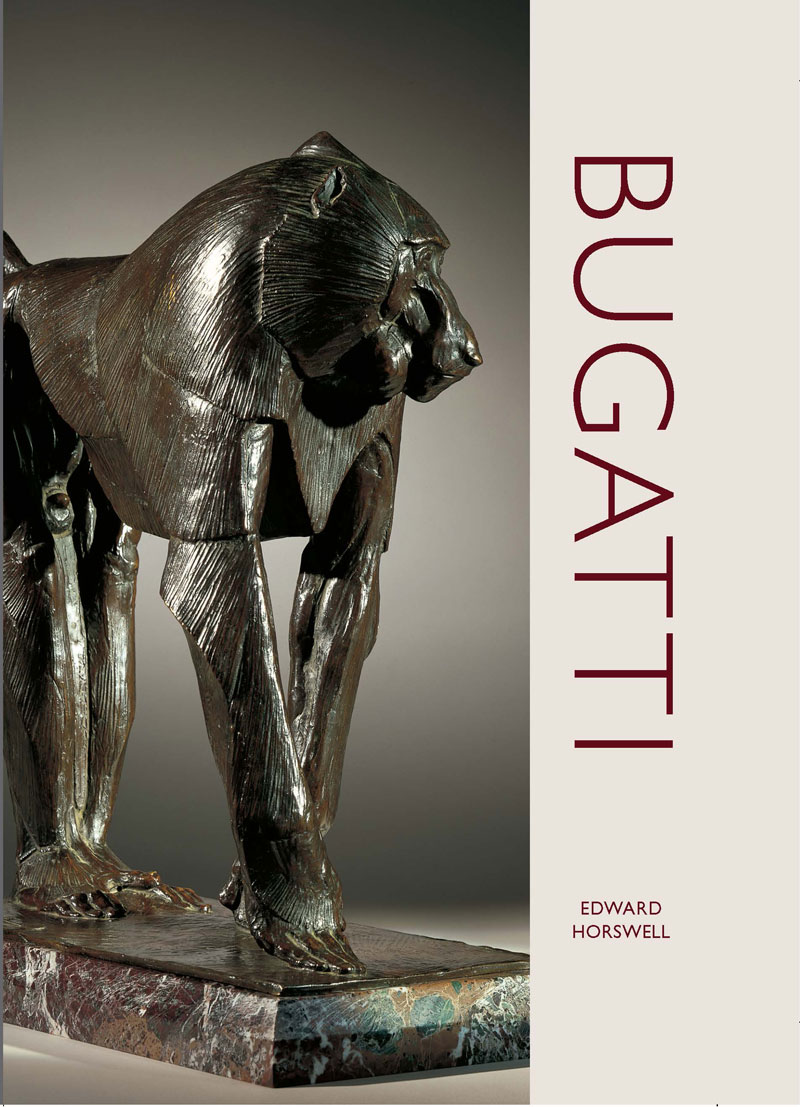

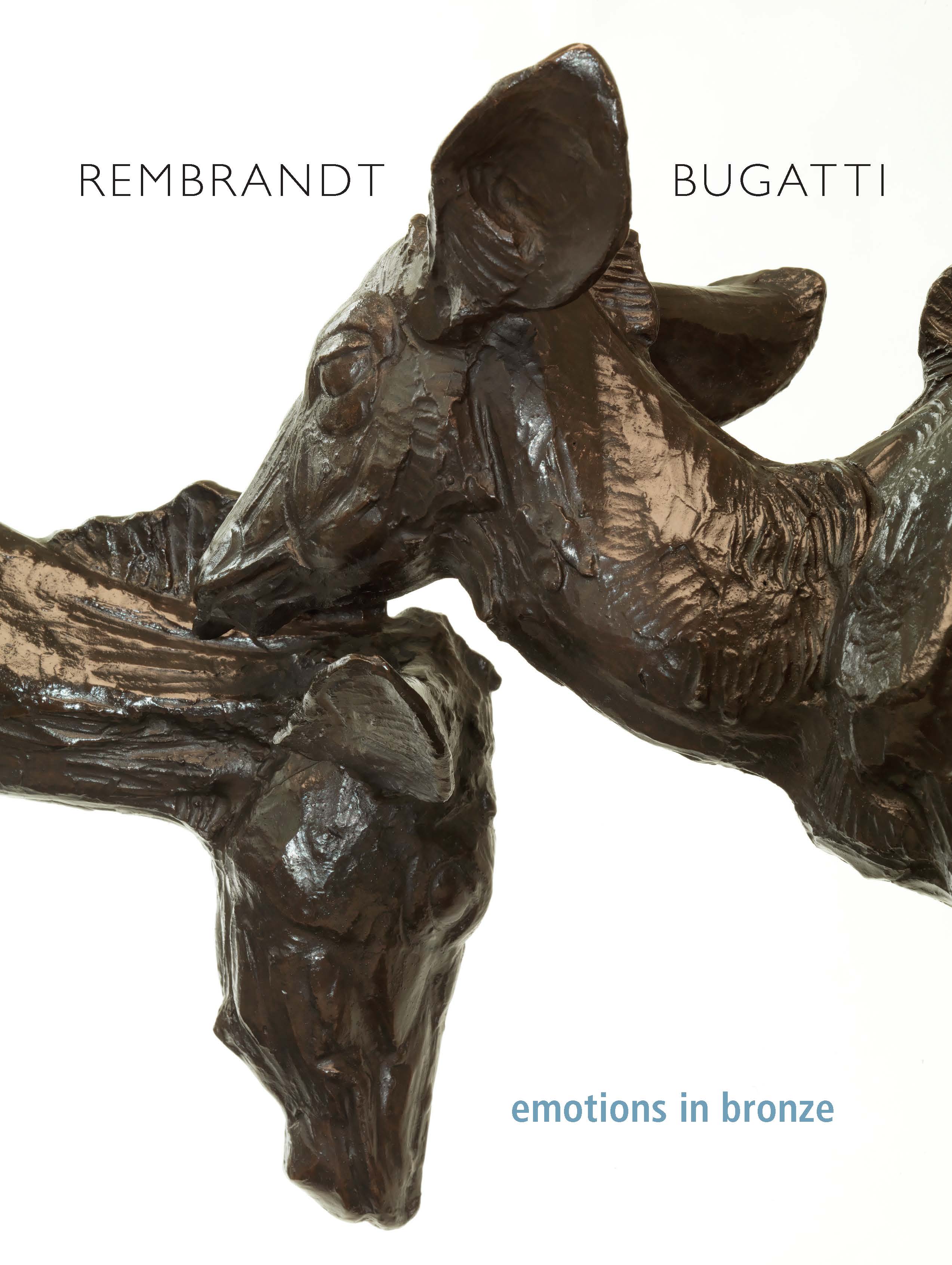

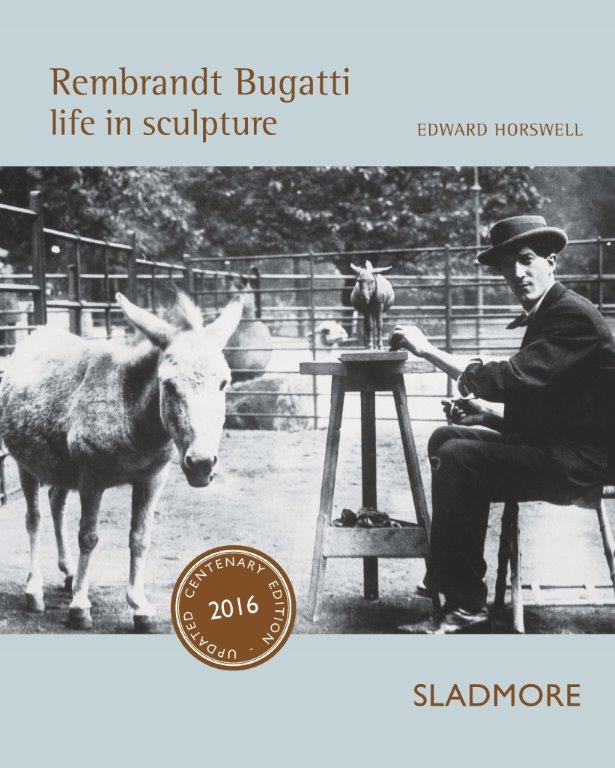

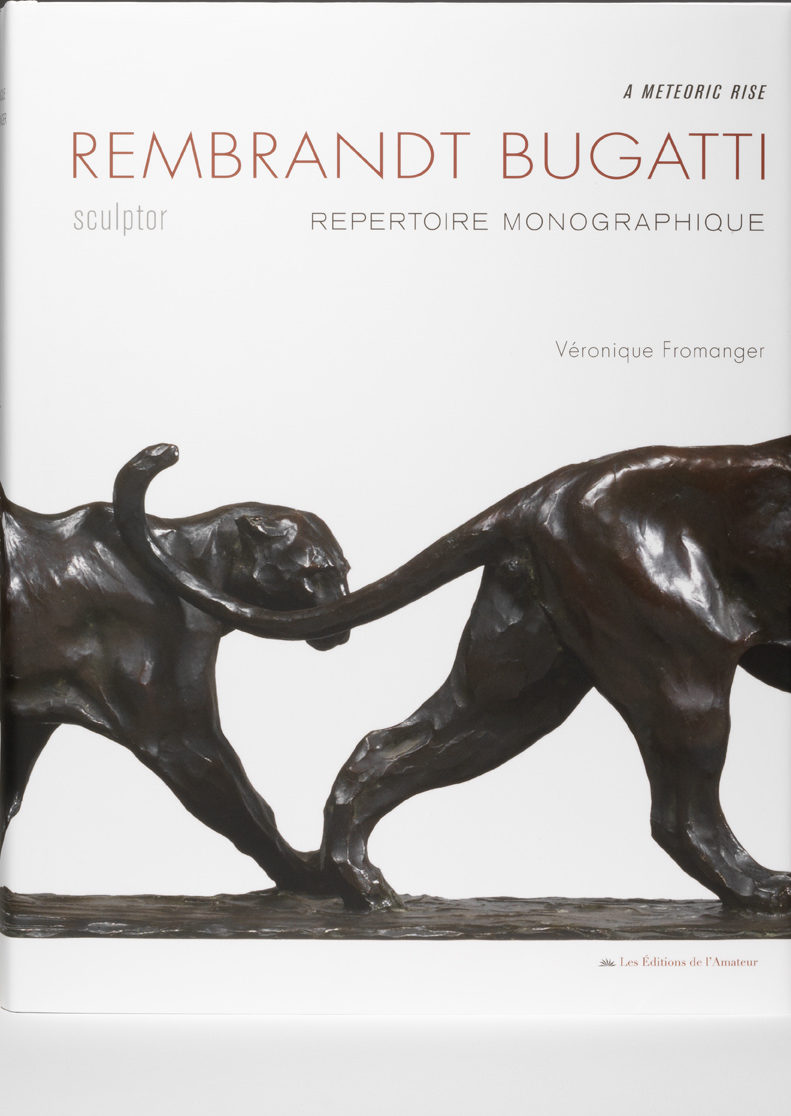

His art combined huge technical finesse, formal beauty, intensity of expression and subtle stylistic inventiveness. Bugatti regularly visited the zoos at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, and Antwerp, and he always modelled his works directly in front of the animals that were his subjects. At the age of nineteen, he came into contact in Paris with the bronze founder Adrien A. Hébrard, and held his first exhibition at the Galerie Hébrard in 1904. He signed a contract of exclusivity that year, and was to show annually at Hébrard’s gallery until 1913. Whereas the modelling of his contemporary Paul Troubetzkoy appeared quick and slick, every mark counted in Bugatti’s brilliantly sculpted pieces. Using plastilene, he pinched, nipped and pressed the material with immense skill. His fingerprints cover the works. Rather than try to depict fur or feathers with scratched markings, he did as Auguste Rodin had done before him, and conjured up a heavily fingered, painterly surface, upon which the light plays to give a sense of life and movement.

By the age of thirty, Bugatti had already built up a large and varied oeuvre of some 300 sculptures. His work gradually lost its Impressionist character and became more heavily structured, built up of parallel ribbons of clay, which act like the painter Paul Cézanne’s hatched brushwork. He seemed the natural successor to Antoine-Louis Barye. But he was by all accounts a difficult and lonely character, and, deeply affected by the First World War and unable to stay in Antwerp where he had spent extended periods, he committed suicide by gassing himself in his Montparnasse studio in January 1916.

Although his work is in the world’s major museums and is highly prized by collectors, Bugatti has only recently begun to be widely recognised in mainstream writing on twentieth-century art. Son of the great fin de siècle designer Carlo Bugatti, who had a huge impact on his talent, and younger brother of the epoch-making car designer Ettore Bugatti, the audaciously named Rembrandt has emerged as a shadowy personality in the history of the European artistic community before the First World War. For too long after his death he was often dubbed ‘the other Bugatti’, since little was known about his life and he did not fit into recognised art-historical movements.

The controversial debuts of Fauvism and Cubism had been concurrent with Bugatti’s own emergence on to the French art scene, and his work was inflected by Expressionist, and even Cubist, traits. He had won the admiration of the celebrated French sculptor Auguste Rodin, attracted the attention of the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire – the great promoter of Pablo Picasso – and been acclaimed by Louis Vauxcelles, the major critic of Cubism and Fauvism. He had affinities with other artists of his generation, such as Amedeo Modigliani in France, Franz Marc in Germany and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska in England, all of whom also died tragically young. Like them, he developed an expressive language, which was drawn partly from the vocabulary of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He also had in common with them a deep understanding of world art, dating back through the ages, and he wished to invest the culture he absorbed in museums with a vitality and freshness he felt in his contemporary life.

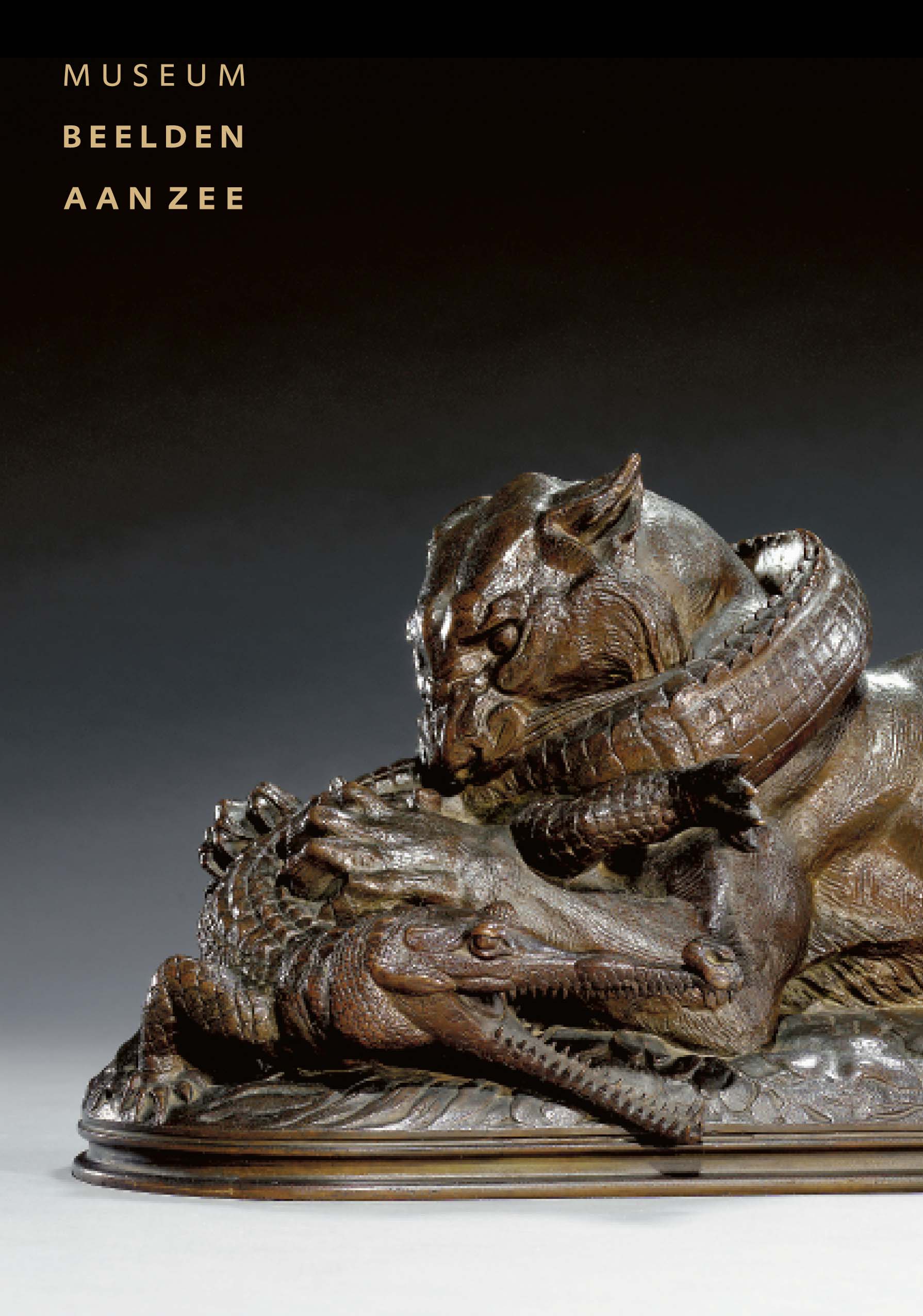

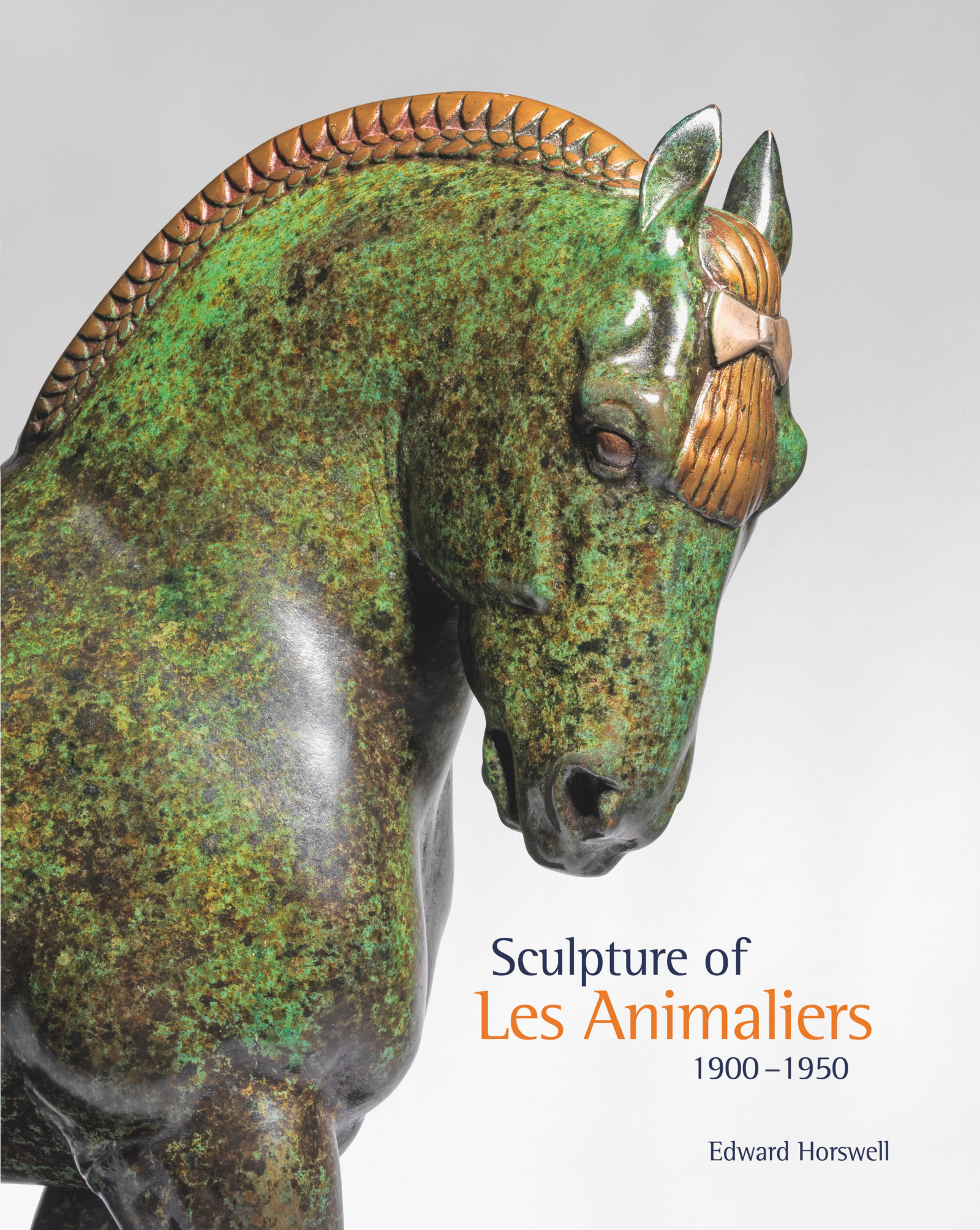

Bugatti knew the grandeur of Renaissance animal bronzes and equestrian sculptures by artists such as Giambologna and Verrocchio. He knew the antique reliefs of Greece and Rome and the mythical horses of the façade of San Marco in Venice. He knew also the nineteenth-century ‘revival’ of animal subjects ushered in by sculptors such as Barye and Emmanuel Frémiet and, of course, by painters like Eugène Delacroix, Jean Louis Géricault and George Stubbs.

Bugatti would bring to this tradition his own vision, empathy with animals and truth to observation. He would surpass the genre of ‘animal art’ and resist all definition as an artist, other than as one who forged his own vision and style. He used animal subjects at once for their own sake and as vehicles for the expression of emotion and the celebration of aesthetic form. He remained aloof from both the avant-garde and the conservative trends of his time. The distinctive, deeply rewarding, sometimes disturbing oeuvre that he created remains unique in art history.

Artworks

View all Artworks >

Crouching Jaguar, 1908

Rembrandt Bugatti

A fine quality, early twentieth century impressionistic bronze model of a ‘Crouching Jaguar’ by Rembrandt Bugatti (Italian,1884-1916). This sculpture was cast in bronze by the […]

Exhibitions

View all Exhibitions >Publications

View all Publications >