Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.

Edgar Degas

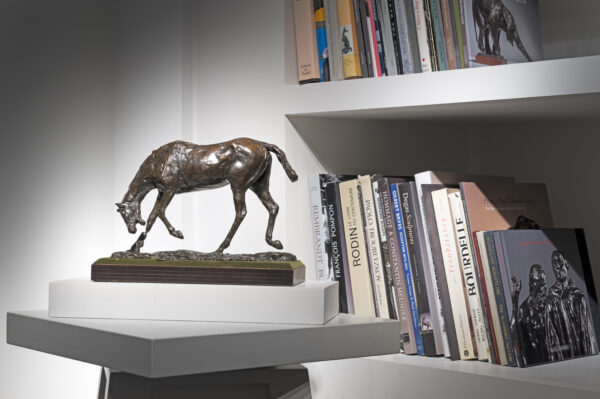

Degas began fashioning wax sculptures from the second half of the 1860s: one of the first was a drinking horse. His fascination with ballet dancers and horses stems from the same central purpose in his art: to banish convention and encompass a far greater range of the elements of experience, including light and movement, than had hitherto been attempted.

Degas’ sculptural practice was little known during his lifetime and was largely private and exploratory but when his studio was discovered after his death in 1917, more than 150 sculptures, mostly in wax, were discovered. Many were badly deteriorated but 72, representing mostly dancers, horses, and women were cast by the renowned Hébrard Foundry in Paris. Degas used his sculptures as preliminary studies for his paintings, they were an integral part of his working practice.

His radical approach to sculpture was both innovative and an inspiration to all sculptors who modelled in plastilene, wax or clay. His sculptures were initially conceived as three-dimensional working drawings, preparatory sculptural notes for his two-dimensional works – in itself a novel approach. Degas’s close observation of his subject gives these horses a rare immediacy, yet they also stand alone as works of great beauty and complete sculptures in their own right.

Edgar Degas was born in Paris in 1834, making him among the oldest of the artists who were to exhibit together regularly from 1874 and become known as the Impressionists.

His father was a native of Naples and his mother of New Orleans, cities where he himself stayed for long periods, his acquaintance with Italy extending to other great artistic centres that also contributed significantly to his formative influences. Enrolled at the Paris Academy of Fine Arts in 1855, Degas did not pursue the Prix de Rome as his father’s relations and his family’s financial circumstances made it superfluous for him to obtain a state bursary to study the Italian masters. He followed an independent path, working first on history paintings that could be included in the Salon, although even these were far from conventional.

After showing there in 1865, he changed course, turning to resolutely modern subjects: dancers, the racecourse, contemporary interiors and scenes of feminine intimacy, experimenting with materials, techniques and conventions of representation. At the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition in 1881, he created a sensation with his Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, a wax sculpture over three feet high that incorporated a real costume and even human hair, prompting remarks that it belonged among the specimens in a natural history display, such was its unexpected realism.

The artist’s own recollection and formal similarities with dated paintings have established that he began fashioning wax sculptures from the second half of the 1860s, among the first of these a drinking horse. Degas’ fascination with ballet dancers and horses stems from the same central purpose in his art: to banish convention and encompass a far greater range of the elements of experience, including light and movement, than had hitherto been attempted. Perhaps the best illustration of his innovative approach is provided by his attitude to the art of the successful academic painter and sculptor, Ernest Meissonier, from whose famous Napoleon III at the Battle of Solferino he derived, using partial copies that he had drawn of the painting, the central figure of a horse in one of his emblematic racecourse pictures. Deriding Meissonier as “the giant of the dwarfs”, he nonetheless admired this artist’s scientific understanding of equine anatomy (Eadweard Muybridge gave an illustrated talk at Meissonier’s studio in 1881) and Paul Valéry recounts that Degas had paused in front of a sculpture of an equestrian Napoleon by Meissonier to explain to him at length how precisely observed it was. In around 1878, Meissonier had, like Degas, made a horse in wax and other materials, including a piece of cloth, as a model to study for his paintings. Through this combination of respect for the skill of the established artist and rejection of the lack of boldness in his work, we can clearly gauge how radical yet securely anchored in the traditions of the past was the new movement of which Degas counts as one of the pioneers.

Degas’ attachment to truth through observation led him to create at least 150 different sculptures in the malleable medium of wax, about half of which were salvaged after his death in 1917, restored and cast in bronze using a technique that allowed minute surface detail to be preserved in the metal. Among these, all of the fifteen horse studies found in his studio were cast and these form a remarkable group, universally recognised as masterpieces ever since their discovery.

Artworks

View all Artworks >

Torso, Woman Rubbing her Back, 1888-1892

Edgar Degas

A fine quality, early twentieth century bronze model of a torso entitled ‘Woman Rubbing her Back with a Sponge’ by Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). This […]

Exhibitions

View all Exhibitions >Publications

View all Publications >